Introduction

|

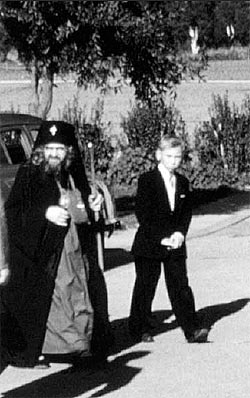

| St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco giving a sermon. Pavel Lukianov, the author, is the acolyte. |

In 2000 he was appointed director of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem, where he served until 2002. He was then assigned as administrator of the Diocese of Chicago and Detroit (now Chicago and Midwestern America). In 2003 the Synod of Bishops approved his consecration as Bishop of Cleveland, which took place on July 12 of that year. He continues to serve the Church as Bishop of Cleveland.

The following reminiscences were written in 1991, three years before the canonization of St. John. These recollections offer us a glimpse into the life of a saint through the eyes of one who spent a great deal of time with him during his last three and a half years of life, and who served with him as his acolyte.

Twenty-five years have passed since the day of Vladyka’s[1] repose. Much has been written about him during that time. I have heretofore not expressed myself in print, thinking that I had no right to pretend that I knew him better than others. I am now doing this for the sake of obedience.

I’m afraid that what has been written in recent times by others has not always corresponded to Vladyka’s character as I remember him. Moreover, Vladyka’s veneration continues to spread, and many know about his miracles, but few know about him personally.

Vladyka knew our family in Shanghai. When my parents moved to San Francisco, my mother corresponded with Vladyka, and he knew me, for all intents and purposes, from the day of my birth.

From my childhood I thought of Vladyka as a holy man. After Vladyka arrived in San Francisco from Europe, whenever we were free from school my mother would bring us to all his services. Vladyka remains in my memory as always joyful and smiling, affectionate with children and attentive to them. As many children as there had been in his Shanghai flock, he never forgot our birthdays or namedays, and always sent congratulatory cards.

At the end of 1962 Vladyka was assigned to San Francisco, and the Lord vouchsafed me to be with him for the last three and a half years of his life.

|

| Bishop Peter of Cleveland |

And so, bless, O Lord!

Vladyka’s now-reposed sister, Lyubov Borisovna Lyubarskaya, once wrote to my mother that Vladyka had grown up as a very obedient boy, and it had not been difficult for his parents to raise him. He was an excellent student, and there were only two subjects that he didn’t like: gymnastics and dance. Vladyka behaved simply, but one could sense his good manners and tact, and he manifested an inner nobility in all things.

When I was a child I heard about an incident that occurred when Vladyka was in the Poltava Cadet Corps. One time the Corps was marching in formation past a church. Misha — such was Vladyka’s name before monasticism — removed his cap and crossed himself. The teacher noticed this, but decided not to reprimand him. However, since one was not allowed to do anything in formation without an order, the teacher considered it necessary to report this to his superior. The latter thought and thought, but didn’t know what to do. Finally, a telegram was sent to Grand Duke Constantine Constantinovich.[2]

There was no reply for a long time, and finally a communication arrived: “Though it wasn’t correct, well done!” Once Vladyka was asked about this in front of me, and he denied this incident. Whether he was denying this out of modesty, I can’t say.

|

| The Lukianov and Bogoslovsky families with St. John, soon after World War II. |

When Vladyka was still in Belgrade he was commissioned by Metropolitan Anthony [Khrapovitsky][3] to write a book,The Origin of the Law of Succession to the Throne in Russia, which was published in Shanghai in 1936. It begins with Equal-to-the-Apostles Prince Vladimir and ends with Tsar-Martyr Nicholas II. It would be good to see this book republished. Not only was Vladyka a staunch monarchist, but he believed that it was necessary to support the authority of Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich.[4] At the daily Divine services he would commemorate the Russian Royal House, and at festal services would commemorate the Grand Duke by name. On special days, such as the Triumph of Orthodoxy, he would commemorate all Orthodox monarchs: Greek, Bulgarian, Serbian, and Romanian.

Vladyka was completely opposed to the substitution for the prayer for right-believing kings at church services with one for “Orthodox Christians.” In particular, in the troparion “Save, O Lord, Thy people,” he insisted that the words “granting to right-believing kings victory over their enemies” be sung.

Regarding the history of the Russian Church, Vladyka had great respect for Patriarch Nikon. I recall that Vladyka was once present in school at examinations on the Law of God. One girl was questioned on reforms in the Russian Church. She answered very well, and at the end Vladyka asked her if Patriarch Nikon was a great man. She, following the traditional views of our textbooks, replied that he was not.

Vladyka, who usually listened very patiently to children, stopped her and said sternly, “No — Patriarch Nikon was the greatest of Russian Patriarchs.” Vladyka likewise highly regarded the works of Metropolitan Peter Mogila.

In Yugoslavia the Maximovitch family, like all the refugees, had a difficult time, and Vladyka helped his family by selling newspapers.

One of his fellow students, who happened to do the same thing, related to me that during lunch breaks he would have to run from one café to another, and only with difficulty would he sell all his copies, while Misha would just stand on the sidewalk, and within a few minutes the Serbs would buy up all his newspapers.

One fellow monk from the Milkovo Monastery in Yugoslavia, where Vladyka received his monastic tonsure, related that Vladyka suffered from stammering since childhood. When he was in Belgrade and had been tonsured a reader, he would come to the Russian Church of the Holy Trinity, put on his sticharion, and modestly stand in the corner of the cliros, waiting for someone to give him something to read.

When Vladyka received the monastic tonsure, this defect went away, and would later only appear when Vladyka was upset. He did not have a musical ear and was slightly thick of speech, but those who were used to it easily understood him.

Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) was once asked who was closest in spirit to him. The venerable abba named only two people: Archimandrite Ambrose (Kurganov), the superior of the Milkovo Monastery, and the young hieromonk John, the future bishop.

Once, when sitting with Vladyka in his cell, I was looking at a portrait of Vladyka Anthony which had been sent from France not long before. (It had been painted by an amateur, but Vladyka told me that he valued it, since the eyes and the expression of the face were just as they were when he had seen him for the last time before his departure for Shanghai. The portrait had been damaged in transit and Vladyka gave it to an artist for restoration. Vladyka reposed before he had a chance to receive it back. I don’t know where it is now.) Our conversation touched upon the metropolitan. After a short silence, Vladyka said that on July 28, 1936 (o. s.), he was sitting in his office in Shanghai when suddenly his heart shuddered. He didn’t attach any meaning to this, but looked at his clock and remembered the time. The next day a telegram arrived, saying that at precisely that hour Metropolitan Anthony had reposed. I had entirely forgotten about this, and only remembered it at Vladyka’s funeral, when Metropolitan Philaret, during his homily, recounted how his own father, Archbishop Dimitry, had once invited Metropolitan Anthony to Harbin. The latter replied that he was now too old to think about any trips, but that he would send in his stead “a piece of his heart,” Vladyka John.

In the early 1970s I once happened to be in Bitol (the city in Yugoslavia in which Vladyka had taught at the seminary) with a group of students from the Belgrade Theological Faculty, and we were having a look at the ancient cathedral church. The rector came and began to show us and explain the noteworthy things in the church. The Serbs, of course, were interested in whether he remembered the former teacher, Fr. Justin (Popovich).

|

| St. John with Pavel Lukianov at the Serbian cemetery in Colma, California, just south of San Francisco. |

Vladyka related to me that his ordination as a hieromonk had been hurried, and that he had not had time to inform his parents. At the time Archbishop Gabriel of Chelyabinsk had said, “That’s all right, we’ll invite them to his consecration.” VladykaGabriel did not live to that time, but it was his panagia[6] that was given to Vladyka John at his consecration. On the day of the consecration, Metropolitan Anthony ordered that Vladyka’s father stand in the altar, so he could watch the laying on of hands upon his son. It was Metropolitan Anthony’s last consecration.

In addition to Russian and Serbian, Vladyka spoke French and German.

How well he spoke them I can’t judge, since I don’t speak those languages myself. However, when a group of Frenchmen came to San Francisco for the consecration of Bishop John (Kovalevsky), Vladyka spoke to them with ease. Vladyka spoke English less well, but understood everything and read it fluently. Vladyka also knew Greek. I was always amazed at how, at Matins, he would do an impromptu translation of the Prologue and several canons from Greek into Church Slavonic.

On feast days Vladyka would say the prayer “O God, look down from heaven …” in Slavonic, Greek, and — in San Francisco — in English.

On weekdays the third exclamation would be in various languages, from Latin to Chinese. The priests on the cliros would make bets as to which language he was about to use.

Speaking of services, it must be mentioned that Vladyka served Liturgy daily — either in his residence at the St. Tikhon Orphanage or at the cathedral. Regarding the main feast days of churches, he did not accept the idea of transferring them to Sundays, but would celebrate feasts on the very day on which they fell according to Church rubrics.

When Vladyka served at the orphanage, he liked to do so in a red phelonion with a woolen omophorion that looked like a scarf. People who didn’t understand the history of church vestments would ask why Vladyka was serving like a priest, or whether he had caught a cold. His schedule was as follows: In the morning he served Matins, then the Hours and Divine Liturgy. After the services, if he had served at the cathedral, he would stop by a hospital on the way home and would visit all the Orthodox patients. When he came home he would occupy himself with business. Besides official business, he used to receive a lot of personal letters, which he would answer himself. (During his three and a half years in San Francisco he received more than ten thousand letters.)

At the top of each letter or postcard Vladyka always neatly placed a large cross. When the letter needed to be folded, I had to see to it that the cross was not creased or put into the envelope sideways or upside down. Vladyka did not permit us to lick an envelope when sealing it, and when opening one we had to use a knife. Vladyka always noted with a smile that only Stalin tore open envelopes.

At three o’clock in the afternoon Vladyka would read the Ninth Hour and, on the required days, the Interhour. If it happened that he was on the road, we would read the Ninth Hour in the car. Before Vespers Vladyka would have a cup of coffee, while on hot days he would have tea with a light snack. Then, either at the orphanage or the cathedral, he would attend Vespers and Compline. At the latter service, up to three canons would sometimes be read. If Vladyka had been at the cathedral, then on the way home he would again visit one of the hospitals.

Vladyka had dinner before midnight, and after this meal he would go to his room for a rest. He ate from one bowl, with one tablespoon, always with a prayer rope in his hand, and he would recite the Jesus Prayer while eating. Sometimes Vladyka would use chopsticks.

From the day of his monastic tonsure, Vladyka slept sitting up. As a result of this he had swelling of the feet and it was painful for him to wear shoes. Therefore, Vladyka wore sandals. At home in his cell, or when he served in the church of St. Tikhon of Zadonsk [at the orphanage], he often went barefoot — not out of foolishness-for-Christ, but because it was easier on his feet.

Abbess Theodora, the now-reposed superior of the Lesna Convent in France, used to relate that once, when Vladyka was at their convent, his feet began to ache very badly, and she called a doctor. The doctor prescribed bed rest. Vladyka thanked him for his concern, but refused to lie down in a bed. No manner of persuasion helped. “Then,” Matushka[7] would say, “I don’t know how I dared to do this, but I told him directly, ‘Vladyka, as abbess of this convent, by the authority given me by God, I order you to lie down.’” Vladyka looked at the abbess in amazement, went off and lay down. In the morning he was already in church during Matins, and with that the “course of treatment” ended.

Once in conversation Vladyka mentioned that in Greece, if a hierarch dies while still ruling, he is buried in a sitting position. I asked Vladyka if he wanted to be buried sitting. Vladyka meekly smiled and gave me to understand that he did. Vladyka Nektary (his vicar bishop) knew about this, and later suffered over it, and several times said that he regretted that he had let himself be talked out of doing this.

|

| St. John, soon after his arrival in San Francisco, with Archbishop Tikhon (Troitsky). The author is at left in front of St. John. |

The opinion exists that Vladyka behaved as a fool-for-Christ. I categorically disagree with this. Vladyka was not of this world, but that’s not the same thing as being a fool-for-Christ.

Once, when Vladyka was leaving the altar after the Liturgy, a man came up to him with business questions, and Vladyka somewhat confusedly gave some answer. When that man went away, Vladyka turned to me and said that right after Liturgy it was hard for him to concentrate on something else. And truly, whoever saw Vladyka in church knows that he was entirely immersed in the Divine services.

In Nun Thaisia’s book Russian Orthodox Women’s Monasticism of the Thirteenth to Twentieth Centuries (published byHoly TrinityMonastery in 1985), on page 11 we read: “The fools-for-Christ’s-sake of Diveyevo were remarkable. This podvig is extremely rare and difficult. It consists in the following: when ascetics — being in the prime of their minds and souls, and having attained a high degree of spiritual perfection, so that the other world is opened to them and they are in contact with angels and conduct warfare with demons in waking reality — when these lofty ascetics take on the appearance of madness (if such is the will of God, and this occurs extremely rarely) in order to hide their exalted gifts of clairvoyance, miracle-working, and love for God and neighbor. They always speak in proverbs and allegorically. But they also take on the appearance of insane people so as to arouse ridicule, revilement, and insults against themselves for the sake of perfection in humility, and by this they conquer the devil more powerfully.” According to the aforesaid, Vladyka could not have been a fool-for-Christ, because he was a hierarch of God, and never could have permitted that great office to be ridiculed. On the contrary, Vladyka regarded his office very carefully.

When receiving anyone officially or traveling anywhere, he always wore a panagia and klobuk. In the street he always walked with a staff.

I remember how once, on the first day of Christ’s Nativity, we were visiting the sick at the municipal hospital. Vladyka was tired, and on that day one of his feet was especially bothering him.We were walking down the long corridors. Vladyka suddenly stopped, took off his sandal, and went on. Those we encountered smiled when they looked at him. I then remarked to him, “Vladyka, they’re laughing at you.”

Vladyka stopped and put on his sandal.

Although Vladyka was a bit awkward in his movements, he always tried to be careful and orderly. On the cliros he always demanded that the service books be set in order, in their own places, and one would have to fold the bookmarks neatly inside the books. He always carefully folded his vestments and required this of others. If an acolyte came up for a blessing to wear a sticharion and it was not neatly folded, Vladyka would not give the blessing.

During the Paschal period Vladyka liked to wear a white ryassa and colored robe with an embroidered belt.

In San Francisco, as far as I can remember, there were seventeen hospitals at that time. Vladyka issued a decree, according to which all the hospitals were allocated among the city’s priests. It was their duty to visit their hospitals once a week, and once a month to present to the diocesan office a list of patients visited. Vladyka himself, over the course of a month, would visit all the hospitals. Those hospitals in which Russians were most frequently to be found he would visit several times a month. Once Vladyka and I were walking through the empty corridors of a hospital and Vladyka remarked that in France, on holidays and Sundays, in contrast to America, the hospitals would be full of visitors.

Many times Vladyka used to appeal to people from the ambo on Nativity and Pascha not to forget the sick on those great days. On these feasts the sisterhood would prepare boxes with treats, and Vladyka would leave a box with each person he visited.

Speaking of feasts, Vladyka always corrected those who greeted him with the words “[I congratulate you] with the feast,” and would say, “Not ‘with the feast,’ but ‘with the Nativity of Christ.’”

After his arrival in San Francisco, Vladyka organized theological courses, which he himself taught along with his priests. Vladyka himself watched over the progress of studies and only permitted lectures to be omitted when there was a Vigil that evening. It was the same with regard to the high school. Vladyka regarded spiritual instruction as strictly as he regarded services: he would dismiss the priest-teachers who sang on the cliros to teach, even on occasions when the services had not yet ended. Vladyka tried to visit the church school daily. He considered it his obligation to be present at all examinations — and not only at the high school, but at the other schools as well. He knew the Menaion and the Lives of Saints, and at examinations always asked what saint a student was named after, when his nameday was, and about the Life of his saint. He would encounter students with names like Capitolina, and Vladyka would know the Life and commemoration day even of saints with such rare names.

Knowing that children were watching him, Vladyka attentively and correctly made the sign of the Cross on himself, bringing his hand up to each shoulder.

Vladyka understood young people, liked to joke, and was always interested in what they were engaged in. Several times he even organized evening parties at the orphanage at his own expense, so that the Russian youth would have an opportunity to mix with each other. I remember how once, after services, Vladyka asked us acolytes what we were going to do.We replied that we wanted to go to the theater to see a film. Vladyka was interested in which one. When he learned that the film was a serious one, I believe a historical one, he gave each of us money for a ticket.

Vladyka realized that young people need some sort of amusement, but he was categorically against soccer. In conversations with young people, Vladyka especially emphasized the necessity of being righteous and of always speaking the truth, and would add, “He who tells a lie will also steal.”

I remember how once Vladyka summoned one of the clergymen. The latter informed him by telephone that he was unwell and could not come. An hour later it turned out that he felt fine and had been seen taking a walk. Vladyka later often repeated, “I never thought a clergyman could tell a lie.”

Vladyka was a hierarch who lived the life and interests of the whole Ecumenical Church. I remember how on July 5, 1963, we were reading the Ninth Hour. I had just read the troparion to St. Athanasius of Mount Athos, and Vladyka stopped me and said, “There’s a great celebration on Athos today.” To my question as to what was going on there, Vladyka replied that on that day the thousand-year anniversary of Athos was being celebrated. This was not an idle observation. It was obvious that Vladyka was on Athos in soul and spirit.

Vladyka always attentively observed what was done in other Local Churches and respected the traditions of others, although he himself followed the Russian customs in everything.

On Great Saturday, after the bringing out of the shroud, Vladyka would go to all the Orthodox churches in San Francisco — Greek, Serbian and others — and would venerate the holy shroud.

During his first months in San Francisco, Vladyka was only the administrator of the diocese, but officially remained Archbishop ofWestern Europe. Until Vladyka was officially assigned to the Western American cathedra, he kept his watch on European time. People who didn’t understand Vladyka laughed at this. But with Vladyka, everything was well founded: while living in San Francisco, he was looking after the life of his flock in Western Europe. I remember how on Great Saturday in 1963 we were divesting Vladyka in the altar after the end of the Liturgy. It was 3 pm, San Francisco time. Vladyka looked at his watch, crossed himself, and said, “In Paris, Paschal Matins has begun.” Vladyka often repeated with a smile that the sun did not obey the laws of America, and therefore in the summer he did not set his watch ahead [for Daylight Savings Time], and his life flowed on in conformance with this: In the summer we read the Ninth Hour at 4 pm, and he would eat dinner at 12:30 am.

Vladyka was emphatically against setting up a Christmas tree at heterodox Christmas [i.e., December 25 n.s.]. Often in sermons he would say that a Christmas tree of itself has no spiritual significance, but since it is connected with the feast of the Nativity, one could not decorate it before then.

Vladyka always tried to see the good in people. When I was already living in New York and working at the Synod, some documents came into my hands connected with the “San Francisco affair,”[8] in which people who were themselves ill-disposed toward Vladyka testified that he spoke very calmly and objectively about his opponents.

I recall now, as if it were before me, how Vladyka twice was present at balls in San Francisco. The first time was after the Vigil at which the glorification of St. John of Kronstadt had taken place. There were worshipers at the cathedral, but not as many as one might have expected on such a day. After a Vigil, Vladyka would usually go to some hospital.

This time, after we sat in the car and the driver asked, “Where to?” Vladyka replied, “To the Russian Center, to the ball.” When we arrived, we went up to the main hall and Vladyka walked around it in silence.

We saw how old people, society figures, literally hid under the table. One woman, seeing Vladyka, cried out with joy and delight, “Vladyka’s come! Vladyka’s come! We have to give Vladyka some tea!” Vladyka looked sternly at everyone, but at the same time I saw that there was no personal anger in him toward any of them. Without having said a word, we left in the same way.

The second time he was “at a ball,” Vladyka demanded a microphone and addressed a sermon to those present. I knew how upset he was with everything, but his speech was calm. The next morning an order was issued to the clergy that all who had been present at the ball the previous night could not take part in the Divine services that day, even if they were acolytes or singers.

Regarding Vladyka’s attitude toward church discipline, I remember the following story: A diocesan bishop reposed. One village priest took part in his funeral. When he returned to his parish, he continued to commemorate the reposed hierarch at the prescribed places as though he were still alive. To the parishioners’ question as to why he was doing this, the priest responded that he had not yet received an order from the consistory. Vladyka used to accompany this story with the observation that, of course, this was something extreme, but that he approved such a strict regard for discipline.

Concerning Vladyka’s asceticism, I can cite the following example: Once Bishop Nektary was driving Vladyka somewhere. There were only the three of us in the car. We heard a siren and Vladyka Nektary stopped, as he was supposed to. Either a fire truck or an ambulance flew by, and Vladyka Nektary recalled how he was once driving Vladyka Tikhon,[9] and in the same way had to stop and let a fire truck pass. Vladyka Tikhon turned to Fr. Nektary (still a hieromonk at that time) and asked him what it reminded him of. The latter said that it reminded him of a bomb alert in Germany, to which Vladyka Tikhon remarked that this was not correct — that this was how evil spirits screamed. Then Vladyka Nektary said to us, “I don’t know how evil spirits scream — I haven’t heard them.” Vladyka John listened to Vladyka Nektary’s story in silence, then said quietly, “God forbid that you should hear how demons scream.” Later Vladyka Nektary and I said to one another that from Vladyka’s words we both got the impression that that he had heard them.

In his personal life Vladyka was quite modest and simple, but in church he was a prince of the Church. At all services except for the Liturgy, Vladyka always stood on the solea, in full view of all.

He always saw to it that the daily Epistle and Gospel readings were read correctly and without omissions. He taught us that one could transfer the daily readings only on the twelve great feasts, as well as on the Nativity of St. John the Forerunner, the feast of the Apostles Peter and Paul, and a church’s main feast day.

Vladyka always demanded that the Symbol of Faith and the Lord’s Prayer be sung by the whole church. For this all the deacons and acolytes would go out to the middle of the church and the senior deacon, facing the altar, would lead the singing.

|

| St. John (center) serving the Divine Liturgy at the Convent of the Vladimir Icon of the Theotokos in San Francisco. Concelebrating with him are Bishop Nektary of Seattle (left) and Bishop Sava of Edmonton (right). The author is next to Bishop Sava, holding the trikirion. |

Vladyka used to reprimand those who moved candles that were placed by others from one candlestand to another, pointing out that these were gifts to God, and should burn where they were placed. Once, in a church at the time of the polyeleos, the deacon had not brought out his candle in time. He took a candle from a candlestand. Vladyka stopped censing and demanded that he replace the candle, and then he waited until the deacon’s candle was brought out. Candles could only be removed from a candlestand when they had finished burning.

Vladyka always strictly made sure that the antimension, the church vessels, the altar table, and the table of oblation were maintained in the proper state of cleanliness. I recall how once Vladyka was serving on a weekday in a parish. When he opened the antimension, Vladyka shook his head and began to collect particles with the sponge. The senior priest, turning to those standing in the altar, asked uneasily, “What did he find there? I specially cleaned everything yesterday.” When he later found out about this question, Vladyka asked, “I’d like to know what he did with those particles. After all, he didn’t serve yesterday.”

During the Paschal week, on Bright Saturday the royal doors were not closed after the Liturgy. Before the Vigil the Ninth Hour was sung according to the Paschal rite. The royal doors were closed at “Lord, I have cried …” at the words, “The doors being closed….”[10] Vespers and Matins at the apodosis of Pascha were performed according to the rite of Bright Week. The Hours were sung, including the Ninth Hour, and with that the apodosis of Pascha was concluded.

At the Liturgy for the Ascension, Vladyka himself would intone the exclamation, “Always, now and ever and unto the ages of ages,” and at that point the priests would remove the shroud from the altar table and set it in the High Place. At the words, “In peace let us depart…”

Vladyka would bless the worshipers.

During the Vigil for the feast of the Entrance of the Theotokos into the Temple, before the polyeleos Vladyka would send me to invite all the three- and four-year-old girls to stand with candles at the foot of the solea. At the beginning of the polyeleos Vladyka would bring the festal icon out of the altar and the girls would accompany it to the analogion, remaining on each side until the veneration of the icon.

|

| St. John sprinkling with holy water at his last Pascha in 1966. Pavel Lukianov is behind his left shoulder. |

During the Paschal period one would have to say, “Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death,” to which Vladyka would reply from his cell, “And on those in the tombs bestowing life.”

After this, one could enter. Vladyka did not permit any conversations in the altar and gave severe punishments for this. The subdeacons always had to be at his side. The person who held the service book had to follow the services and turn the pages himself. If one of the acolytes was guilty of something, Vladyka would reprimand him after the service and would lovingly, affectionately, knock him on the head with his staff, adding, “A hierarch’s staff is attracted to a foolish head.” Regarding his staff, Vladyka never allowed it to be brought into the altar, and would say to us acolytes that there are angels in the altar, and a bishop cannot shepherd them.

Vladyka was strict with us, but also considerate. He never sat down at a festal table if there was no special table for the acolytes. Once, in 1963, there were six bishops serving on Vladyka’s nameday. The sisterhood made an effort to arrange a sumptuous table for the bishops. After the prayer, Vladyka noticed that there was no place for the acolytes. Calling me over, he gave me the keys to his residence, and gave us all the best food that was on the bishops’ table. After this incident, at all parishes there was a place for the acolytes at all meals.

Vladyka did not allow acolytes to wear ties during services. He pointed out that if in extreme circumstances a priest can use a thread in place of an epitrachelion, then it follows that an acolyte should not have a tie around his neck during services. I have frequently had occasion to observe the unusual practices of certain priests, which they justified by saying that Vladyka John had acted that way. Zeal is a praiseworthy thing, but why should one justify one’s own inventions by citing Vladyka? I also happened to read that Vladyka would bless the pilot when he boarded a plane, and similar things. I accompanied Vladyka to the airport almost every time he flew out of San Francisco, and used to fly with him myself, and such a thing never happened.

Vladyka would simply sit in his seat and would of course pray privately, but would not attract attention to himself by anything outward. One hears especially much about Vladyka’s supposed predictions about the end of the world. In particular, people say that in 1962, as he was entering a church he stumbled and fell, and when he arose said, “Antichrist has been born.” And there were many other things like this. Of course, I was not with Vladyka twenty-four hours a day, and cannot state categorically that such things never happened. However, first of all, in my experience this was not like Vladyka. Second, Vladyka came to San Francisco only at the end of 1962. Third, Vladyka was asked about Antichrist more than once in front of me, and he never confirmed that he had already been born.

Vladyka said much about Russia, but that would require a special article. Here I will only mention what he used to say about Russia’s rebirth: “If the Russian people repent, it is in God’s power to save them.”

|

| Pavel Lukianov reading the Psalter at St. John's coffin. |

Three days later Vladyka reposed. My mother told me, “All your life you’ll remember Mama.” And how right she was! But, evidently I wasn’t worthy. The day before his departure Vladyka, in front of me, called the editors of the newspaper Russkaya Zhizn (Russian Life) and, by telephone, gave them an announcement that on the eve of the feast of the Nativity of St. John the Forerunner and on the day of the feast itself there would be a triumphant, festal hierarchal service. Vladyka specifically emphasized the words “triumphant and festal.” Vladyka reposed on June 19. This announcement was never published, but those who were in San Francisco on June 24 at his funeral, on the day of the commemoration of St. John the Forerunner, can themselves testify that the service was truly triumphant and festal. This was not a day of grief — this was the day of Vladyka’s triumph. I beseech the Lord, by the prayers of Vladyka, that I will fulfill even a little of what I learned from him. Amen.

02 / 02 / 2009

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий